1 MRI: Fruit Quality Measurements

Michael J. McCarthy, Young Jin Choi and Siwalak Pathaveerat

Department of Food Science and Technology

University of California, Davis, California USA

INTRODUCTION

The quality of fruit depends upon both the external and internal

fruit properties. The properties of fruit may vary as a function

of weather, harvest conditions, natural biological diversity

and handling conditions. Fruit purchasers such as retailers

and consumers desire a uniform known external and internal

quality for each fruit. Current state-of-the-art sorting and

sensing technology is primarily focused on external surface

quality features like color. External quality features are

assessed for each and every fruit using automated color sorting

equipment. In contrast, internal quality features are generally

assessed off-line by taking a sampling of fruit for destructive

testing. As the fruit market becomes more competitive and

international there is a greater need to determine internal

quality of fruit to successfully meet market demands and limit

losses. A shipment of citrus fruit that contains a single

fruit infected with a green mold can result in damage to the

entire shipment. This type of damage results in rejection

of the lot and a significant economic loss on the shipment.

Additionally, the fruit producer who sent the mold contaminated

shipment potentially looses the customer to a competing fruit

producer. This type of scenario has increased the interest

in new internal quality sensors that are nondestructive and

can operate at fruit sorting line speeds of 8-12 fruit per

second. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been

shown to be an effective method to measure internal fruit

quality (1, 2) and can theoretically operate at the required

speed.

MRI has been demonstrated to be sensitive to a large number

of internal defects and quality factors in fruit including

insect damage, bruising, dry regions, browning and maturity

(1, 3). These quality features and defects are quantified

in MRI using differences in spin-spin relaxation time, diamagnetic

susceptibility, diffusion coefficient, and signal intensity

(4-9). A recent review by Hills and Clark summarizes defects

and quality parameters that have been measured using nuclear

magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1). While MRI has proven

successful at detecting quality attributes and defects additional

knowledge is needed to actually implement an in-line MRI based

sensor. These steps include the design of suitable hardware,

development of sensitivity scales between MRI parameters and

fruit quality attributes, and testing season-to-season as

well as growing location impact on the developed sensitivity

scales. The development of data on seasonal and growing location

impact on MRI parameters, the automated detection of a defect

and the internal spatial variation of fruit properties will

be presented as examples of the next stage in development

of MRI for sorting fruit. These examples will be demonstrated

through detection of freeze damage in Navel oranges, detection

of mold damage in citrus peel and the variation of composition

within an avocado fruit, respectively.

………….contd.

Last paragraph of conclusion

of this chapter………..

The distribution of oil and water and hence the spatially

localized maturity of an avocado varies significantly. Achieving

an accurate determination of the average maturity in the fruit

by any measurement technique depends upon the volume of the

sampled flesh. Ideally the entire flesh would be measured.

However for on-line sensors and off-line tests the actual

volume sampled is usually much smaller than the entire fruit.

Consider the case of measuring percent dry matter of an avocado

using the standard microwave drying technique, where only

a small section of the fruit is used for determination of

the percent dry weight. This method uses a thin longitudinal

slice a few mm thick. The result of this procedure could easily

be influenced if the thickness of the slice were not uniform

(e.g. calyx end thicker than stem end). Likewise the NMR technique

determined value can be influenced by what volume is sampled.

Table 8 shows the variation in measured maturity level as

a function of sampled volume size in the chemical shift image.

Each pixel in the image represents volume of [(7.0/32) (7.0/32)

0.2] cm3. As the volume of the measurement is increased the

value of the measured maturity increases towards the average

value for maturity of the avocado. The table demonstrates

that a volume with ~ 2 cm diameter is insufficient to accurately

predict the intensity of the entire slice. The data in Table

8 also explains the results obtained by varying the diameter

of surface coil (results not shown).

References:

1. Hills BP, Clark CK. Quality assessment of horticultural

products by NMR. Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy 2003:50:76-120.

2. McCarthy MJ. 1994. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Foods.

Chapman &Hall. New York, NY.

3. Chen P, McCarthy MJ, Kauten R. NMR for internal quality

evaluation of fruits and vegetables. Trans. ASAE 1989:32:1747-1753.

…………….contd

till end of 18 references.

(IMAGES:

Out of 9 figures - figure 5 is given below)

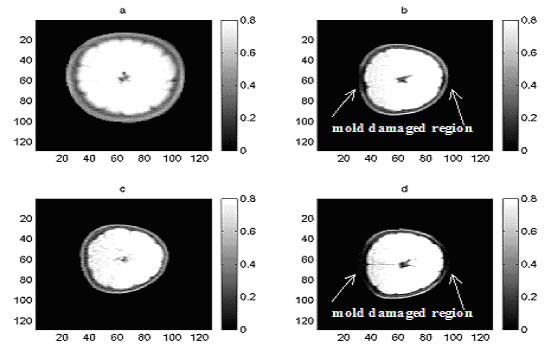

Figure 5. MRI orange images: (a) and (c) for good quality

fruit, and (b) and (d) for mold damaged fruit.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

4 Functional NMR : PLANTS

Markus Rokitta

School of Integrative Biology, The University of Queensland,

St. Lucia, QLD 4072, Australia

and

Universität Würzburg, Experimentelle Physik V

Am Hubland, 97074 Würzburg, Germany

INTRODUCTION

Of all resources a plant needs, water is the most abundant

and at the same time the most limiting one for agricultural

productivity [1]. Therefore, an understanding of the mechanisms

of water uptake and water loss are of particular interest.

First theories about long distance water transport mechanisms

in plants arose with the cohesion theory more than a century

ago [2]. One might expect that all aspects of this problem

have been understood since. However, there is still a very

controversial discussion going on in the very latest literature:

see [3] and reply in the same issue as well as [4,[5,[6].

NMR imaging is particularly suitable for measurement of functional

parameters such as flow due to its non-invasive nature although

the obtainable resolution does not reach the resolution of

optical microscopy. In this context functional means that

physiological parameters can be investigated dynamically over

time. During an experiment one can alter certain conditions

and observe the plant's response to these changes.

ADVANTAGES OF MRI FOR PLANT EXPERIMENTS

The advantages of NMR as compared to other imaging methods

include non-invasive monitoring of anatomy, solute distribution

and time dependent changes of active and passive transport

of substances (water, ions, primary and secondary metabolites)

in plants. No special preparation of the sample is necessary

so that plants can be examined under controlled external conditions

like humidity, temperature, illumination, nutrition and so

on without perturbance by the measurement itself. All parts

of the plant are accessible at any stage of their development.

Advantages of NMR should be obvious when applied to transgenic

plants. The effects of a genetic modification on plant anatomy,

solute transport, metabolism and ways to compensate for genetic

defects can be studied at the quite different level, inaccessible

for other techniques. However, while the spatial resolution

of NMR at the current state of the art is approximately ten

times less compared to optical microscopy, NMR should be seen

as complimentary to other techniques. Meaningful applications

of plant NMR must therefore take advantage of the integrated

observation of intact plants. There are a number of fundamental

questions in plant biology that need to be addressed with

the non-destructive, in vivo, contact-less NMR technique:

How are solutes (water, sugar, lipids, amino acids, ions)

distributed in plants and how is solute distribution related

to structural and functional characteristics of tissues during

development and under stress conditions at the whole plant

or whole organ level?

How does structural and metabolic crosstalk of different organs/tissues

occur within an interactive system, for example within the

seed (seed coat - endosperm - embryo)?

What forces and mechanisms play a role in water and solute

transport in plants?

What effects have genetic modifications on the intact plant?

What compensation mechanisms exist for genetically modified

plants?

………….contd.

(IMAGES: Out of 7 figures - figure 5 is given below)

Figure5

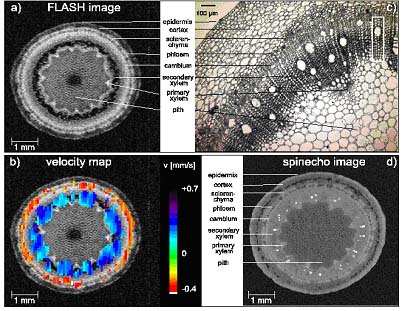

Figure 5: Cross-sections of the shoot of a 35 days old intact

and transpiring castor bean plant made by NMR micro-imaging

(a, b, d) and light microscopy (c). (a) FLASH image with a

spatial resolution of 47 m; (b) flow velocity map superimposed

on the previous image; (c) light microscopy; the size of one

pixel in NMR flow imaging (b) is indicated in the upper right

corner of the picture. (d) spin echo image with a spatial

resolution of 12 m. Reproduced from Rokitta et al., Protoplasma,

209:126-131, 1999 [33]

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

19. MR of Lung

David C. Ailion and Gernot Laicher

Department of Physics, University of Utah, 115 South 1400

East, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112

Even though lung is one of the most important organs in the

human body, in the past it has received relatively little

magnetic resonance study. However, with the advent of hyperpolarized

gas NMR imaging, this situation is changing. Proton imaging

has been particularly difficult, primarily for two reasons:

(1) the presence of air-tissue interfaces in the outer (alveolar)

portion of the lung results in severe internal inhomogeneous

broadening of the NMR line which can cause blurring of the

image and (2) the lung is a relatively low density object

which is near much higher density objects (the beating heart

and chest wall) that are moving asynchronously, thereby causing

severe motional artifacts. In this Chapter, techniques are

presented for overcoming both these difficulties in proton

imaging. In particular, asymmetric imaging (as a way to utilize

the inhomogeneous broadening to gain information about lung

microgeometry) and techniques like the rapid line scan and

radial and spiral k-space acquisitions (for reducing or eliminating

motion artifacts) are described. In addition, MRI of hyperpolarized

(hp) gases (3He and 129Xe), which provides an alternate approach

that is much less sensitive to inhomogeneous broadening, is

explained. Applications of NMR to the study of restricted

diffusion of water molecules are presented in which the diffusion

of water within different microscopic compartments can be

distinguished. Finally, applications of these magnetic resonance

techniques to the study of lung diseases like pulmonary edema

and emphysema are discussed.

I. INTRODUCTION

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has made enormous contributions

to medical diagnostics in recent years and has become one

of the major weapons in the physician's arsenal for detecting

and diagnosing diseased regions of the human body. Even though

lung is one of the most essential organs in most animals,

with lung disease being responsible for hundreds of thousands

of human deaths each year, there have been relatively few

applications of MRI to lung, primarily because of technical

difficulties that are peculiar to the lung. These difficulties

arise primarily from three sources: (1) inflated lung has

a much lower water density (approximately 20% that of free

water) than do other biological tissues and will thus be characterized

by a correspondingly smaller proton NMR signal; (2) the NMR

line shape in the outer, mainly parenchymal region (i.e.,

containing the alveoli) is inhomogeneously broadened; and

(3) the NMR image of the lung (a relatively low-density object)

may be affected by the asynchronous motions of nearby high-density

objects (the heart and the chest walls). The inhomogeneous

internal line broadening can cause a blurring of the NMR image

unless special imaging techniques are employed. In Section

II, we discuss the physical origins of this phenomenon and

also describe techniques that will utilize this feature to

allow the imaging of the inflated regions of the lung. The

asynchronous motions of the heart (due to beating) and the

chest wall and lung (due to breathing) give rise to severe

non-local motional artifacts (ghosts) in many MRI applications

(typically those employing the 2D imaging or spin-warp technique).

Several techniques for minimizing these errors will be discussed

in Section III. Section IV describes relaxation time (T1,

T2, and T1?) measurements and techniques as well as possible

mechanisms responsible for these relaxation times. Section

V describes pulse gradient techniques for studying diffusion

with NMR and summarizes the results of measurements of diffusion

of water molecules in lung. These include data acquired using

pulsed magnetic field gradients of moderate strength (~20

gauss/cm) as well as data obtained using ultrahigh static

field gradients (~ 1 Tesla/cm); the results reflect the motion

of water molecules within compartments of different dimensions.

NMR measurements in lung have usually involved proton resonance

and have been limited primarily to NMR in the lung tissue.

Conventional NMR of the airways and gas-exchanging regions

(bronchi, alveoli, ducts) has been very difficult because

of the very low molecular density in the vapor phase. However,

in the last 5-10 years a very promising approach has been

developed for enhancing the NMR signal for certain nuclei

(3He and 129Xe) and has resulted in improvements in the NMR

sensitivity of 4-5 orders of magnitude for these nuclei. The

hyperpolarization (hp) technique, which is described in more

detail in Section VI, involves the transfer of polarization

from laser-polarized electrons of an alkali metal (Rb) to

a noble gas nucleus (3He and 129Xe).

Section VII is a brief summary of some of the medical applications

of the NMR techniques described earlier in this Chapter.

A comprehensive presentation of conventional (i.e., not using

hyperpolarized nuclei) NMR and MRI studies of lung, including

medical applications with emphasis on pulmonary edema, is

given in the book, Application of Magnetic Resonance to the

Study of Lung, edited by A.G. Cutillo [ ]. A brief summary

of lung NMR can be found in an article, "Lung & Mediastinum:

A Discussion of the Relevant NMR Physics", in the Encyclopedia

of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance [ ].

…………….contd.

There

are 100 references.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Some images from the book

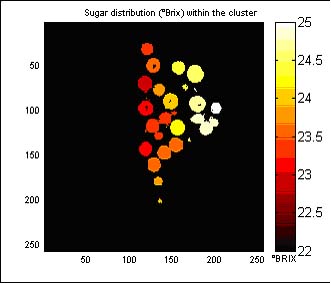

Figure 7 from Ch.2 Wine Grapes - Sugar content is shown as

different intensities of shading.

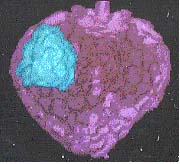

Figure 3 from Chp 6 - Evolution of MRI : Flora To Fauna

Surface rendered images of strawberry fruit infected by Botrytis

cinerea. Image (a) after one day; Image (b) after 2 days.

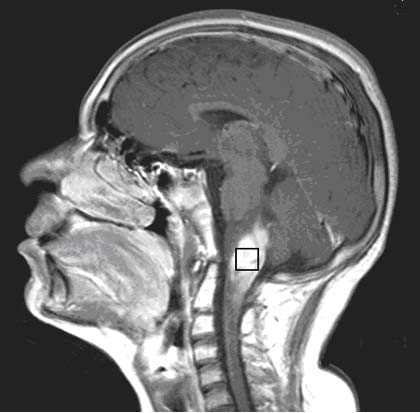

Fig. 2 from Chp-16MR Spectroscopy in oncology

(A) T1-weighted sagittal contrast enhanced MR image of a patient

suffering from brain stem glioma showing the voxel location

from which the proton MR spectrum is obtained.

(B) Water suppressed proton MR spectrum from an 20 x 20 x

20 mm3 voxel recorded using PRESS sequence that an echo time

of 270 ms with a repetition time of 2 s.

|